Many of the plug-in hybrid (PHEV) drivers in the Recurrent community are diligent about plugging in at night and using “all-electric mode” as frequently as possible. We hear reports that our drivers rarely fill up the gas tanks on their PHEV, essentially using them as a short range EV, with 20-40 miles of battery range.

For some other drivers, the “electric” part of the PHEV is rarely used. In this case, they are actually worse than regular, mild hybrids, and as bad as some gas cars. Why is this true? The battery packs in PHEVs make them heavier than gas cars and HEVs, so they require more fuel - aka gas - to run in “ICE” mode.

.webp)

An overwhelming number of studies agree: PHEV’s green credentials don’t match what is advertised. Whether or not PHEVs are green vehicles depends heavily on who is driving the car and how they think about the technology.

Why do people like PHEV?

Plug-in hybrids dispel many of the anxieties new EV drivers have about going all-electric, and can offer an easy entry to an electric drivetrain, including:

- Cheaper to buy than a battery electric vehicle (BEV), but cheaper to operate than a gas car

- Smaller batteries use fewer mined materials (e.g. lithium) and have a smaller initial carbon footprint than a BEV

- Car makers can leverage existing factories, unions, materials, so they can be cheaper to produce en mass

- No range anxiety or charging worries for drivers

- The potential to drive emission free for daily tasks and errands

But the last selling point is the rub. While PHEVs are considered “clean vehicles” per federal regulations and tax code (i.e. they are eligible for many rebates), PHEVs are only clean if you actually plug them in.

You have to drive PHEVs like a BEV in order to get the benefits of a BEV.

The thing is – most of the time, people don’t. Even the testing procedures that calculate PHEV emissions and fuel economy grossly overestimate how “green” PHEVs are. And those calculations can lead people astray about environmental impacts and cost of ownership. Moreso, they may make “green car” rankings, such as those by the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE), less accurate, since they rely on reported emissions and fuel economy data.

How much less clean than advertised are PHEVs?

Quite a bit.

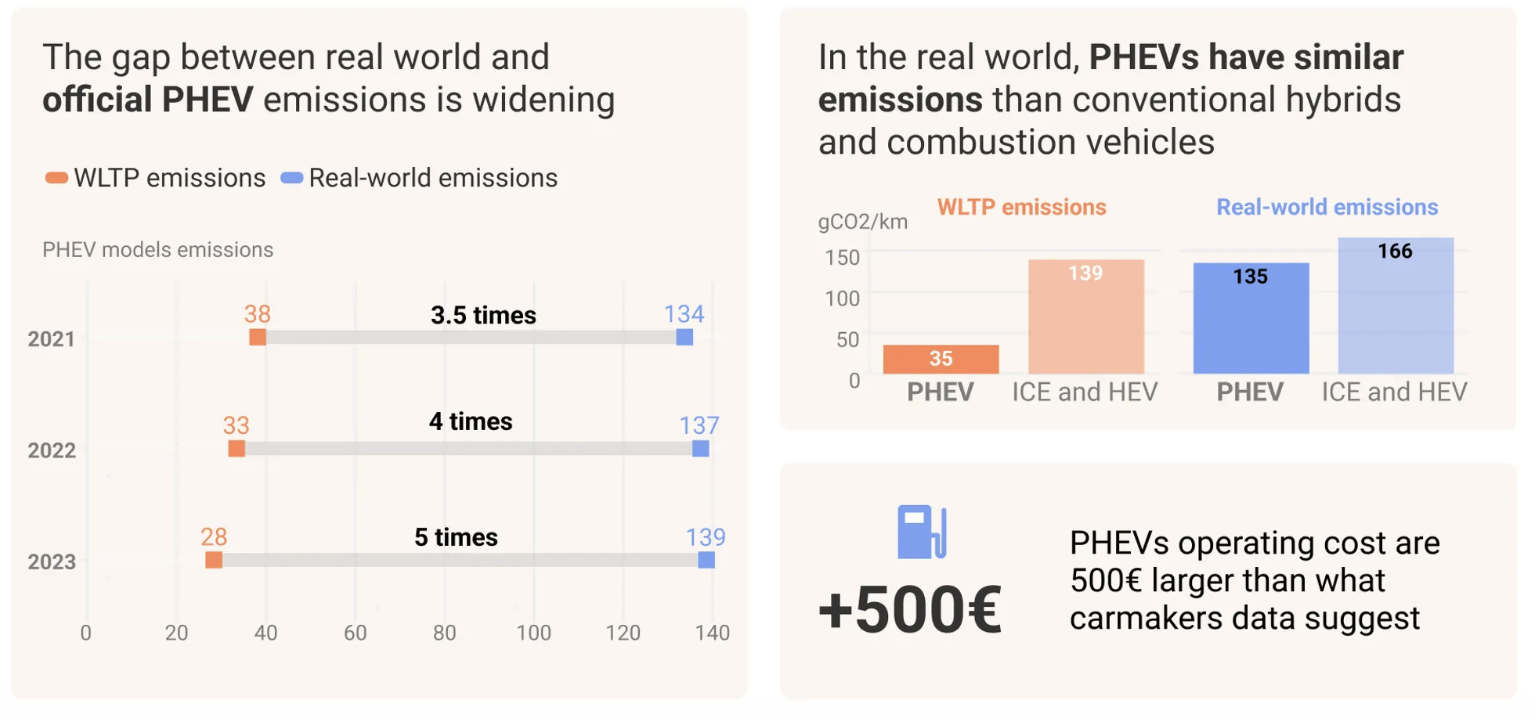

A recent study by Transport & Environment tested 800,000 cars to find that PHEVs pollute five times as much as advertised, even under updated testing protocols.

This report largely agreed with previous results from the The European Commission (chart below). The discrepancy between actual emissions and advertised emissions comes down to how the advertised emissions are tested, as well as when the gas engines kick in.

In most of the world, this testing is done by the Worldwide Harmonized Light Vehicles Test Procedure (WLTP), which is like the EPA in the U.S. They run standardized test procedures to see how much electricity and gas a car will use under "normal" use, and how much CO2 will be emitted. However, like the EPA, the WLTP has to make assumptions about how cars will be driven and used. It turns out that they overestimate how often PHEVs are driven in "charge depleting," or "electric" mode. The guidelines for electric mode were updated recently, but the latest report says they still come up short.

Another issue is that gas engines "assist" the electric motor far more than expected. When drivers accelerate, go uphill, rely on the heater -- all these situations that demand extra power from the car can trigger a gas assist.

Different Drive Modes, Different Emissions

Even the most diligent PHEV drivers may not realize that there are certain driving modes for many cars, and that the specifics of your transmission may dictate whether your car is ever really emissions-free.

- Charge depleting (CD) mode - this is the mode that is closest to a real electric car. The battery is propelling the vehicle. In some models, there is help from the gas motor to accelerate quickly or go uphill.

As per EPA guidelines, cars should have minimal fuel consumption in CD mode, but several studies have found that automakers often underestimate how much fuel is actually used (Bieker et al., 2022; Dornoff, 2021a). In these cases, CD mode is “dirtier” than advertised.

- Charge sustaining (CS) mode - this is when the gas motor keeps battery charge steady while driving. The gas engine, rather than the battery, is the primary propulsion system. While the battery may assist the fuel economy of the vehicle, in the best case, the car is acting as a mild hybrid.

- Charge increasing mode is when the gas engine drives the car and recharges the battery. This can lead to higher fuel consumption and higher emissions.

In some cars, the driver can switch between CS and CD mode, while in many cars, putting on the “sport” or “transmission” mode will switch it into CS mode. Things like ambient temperature may make emissions higher, too.

A Path Forward: EREVs

One worthwhile note that many studies point out is that models like the Chevy Volt or BMW i3 can actually be as green as advertised. This is because the engine is designed as a “range extender” system, and not a primary propulsion system, so they run exclusively on battery power (pure CD mode) until the battery is depleted. The gas engine alone cannot drive the car. These models often achieve their EPA ratings for emissions and fuel use.

Going into 2026, more auto manufacturers in the US are investing into range extended technology in order to combat range anxiety and electrify body styles like trucks and SUVs, which can be hard to make affordable with batteries alone. Since these models often have 70-100+ miles of emissions free, electric range, they may be a path forward to a greener future, although the latest report from Transport & Environment remains cautious.

.webp)

-p-500.png)